Understanding Decision-Making and Patterns of Social Connection in ARTSSCI 4MN1

This winter, four Arts & Science grads returned to the Program to teach two of its experiential “Local Exploration” courses. Jackie Brown (2014) and Ros Pfaff (2013) taught Patterns of Social Connection in the City, while Daniel Carens-Nedelsky and Leanna Katz (2012) taught Theories of Decision-Making and Judgement: A Practical Course for the Indecisive Artsci. Jackie, Ros, Daniel, and Leanna sat down to discuss their courses, their experiences teaching ARTSSCI 4MN1 on Zoom, and what they learned teaching current Artsci students.

Give us the elevator pitch for your course.

Jackie: This was our fourth time teaching the course, and we changed it fundamentally this year. Previously, we focused on urban placemaking, and we would take students on site visits around Toronto—we visited Regent Park and discussed the politics of neighbourhood revitalization; we went to Brick Works and talked about urban agriculture. This year, we honed in on patterns of social connection (and division). Drawing out themes of loneliness and social isolation, we looked at spatial segregation and how urban planning and design have often produced exclusion. We also wanted to make it personal, given what students are going through in the pandemic, and tried to find ideas that would resonate in a semi-experiential way, even if the course was virtual.

Daniel: Our course focuses on decision-making from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. Starting with law, we look at how judges make decisions based on legal, institutional, and other constraints, as well as their values. Then we look at psychology and behavioral economics. We explore some of the better documented decision-making fallacies, including common errors people are subject to, and how environment and stress affect decisions. New this year was a unit on algorithms and machine decision-making. We looked at how machines make decisions, and how human bias often creeps in. Our final unit reframes decision-making, drawing on feminist scholarship to consider decision-making as fundamentally relational. We also thought about gendered decision-making, in the sense that males are often considered the default for whom decisions are made.

Leanna: We tried to tie each unit to students’ personal experiences making decisions and grapple with difficult decisions they’re facing.

What is your favourite part of the course? And the students’ favourite?

Ros: I like seeing the students make connections to their experiences, and consider what ideas from the course could mean in their own neighbourhoods.

Jackie: The students’ feedback was that the course helped them become better observers of their urban environments. For example, some remembered hearing about the Regent Park revitalization — a controversial neighbourhood redevelopment project in Toronto — in the news, but didn’t necessarily think about it from a critical perspective. The course encouraged them to question whether the needs and desires of existing residents could have been better incorporated into the process and outcomes.

Ros: Many students also looked back on their own relationship to the city during childhood and high school, reflecting on their access to parks, public spaces, and other amenities. Seeing students make sense of these urban patterns in the context of course material was really rewarding.

Jackie: This year forced us to focus the content more sharply since we couldn’t visit sites in person. One of my favourite parts was our new emphasis on socio-spatial inequalities, which we demonstrated through visualizations and maps of how resources are unevenly distributed. Some inequalities are more obvious, like income and COVID cases. But we also talked about metrics like shade and internet access, which are more heavily concentrated in wealthier neighbourhoods. We talked about Bogotá, Colombia, for example, where slums are located on the outskirts of the city, physically separated by their location on a mountainside. Public transportation was ineffective and buses traveled slowly because of the steep, winding paths. The city’s solution was to develop a network of cable cars, and it halved commuting time for many people. This provided a positive touchpoint for how problems can be addressed in a way that is tailored to local context. We were deliberate about offering students tools, not only to critique, but to develop solutions.

Leanna: I have many favourite parts. First, decision-making can be stressful, and the students seem to appreciate having a space to think and talk about their experiences, and I love having those discussions with them. In terms of course content, the reading by feminist legal scholar Jennifer Nedelsky anchors my thinking, and seems to resonate with students. She describes one difficulty in exercising judgement as stemming, not from a deficiency in knowing one’s own needs or desires, but from belonging to multiple communities, which can give rise to conflict between different aspects of our identity. Finally, the “embodied decision-making” activity is quite special. It’s an exercise where we invite students to physically move in space and feel changes in their body as they explore a decision they’re facing. I like that it pushes students to integrate multiple forms of intelligence.

Daniel: I like that we provide several types of “readings” — including podcasts, which do a great job of conveying dense and complicated ideas in a pithy way. I think different modes of learning help make the course experiential, even if students are learning from home.

Leanna: Students called the podcasts “listenings,” and told us they really enjoyed them!

What are some interesting intersections between the two courses?

Ros: The module in your course on gender bias intersects with our examination of how cities marginalize and exclude different populations — not just women, but also other groups. For example, we discuss how ”hostile architecture” can prevent individuals experiencing homelessness from sleeping in public spaces as well as how processes of gentrification or neighbourhood revitalization projects may often exclude low-income communities.

Jackie: Also, the idea you referenced about relational decision-making made me think about how decisions come about in a community context, and the challenge of synthesizing different inputs. A key theme in our course, and in urban planning, is how to take conflicting perspectives into account, particularly when decisions will affect so many people.

Daniel: Your course also relates to the podcast we discuss by psychologist and behavioural economist Dan Ariely, where he talks about designing decision-making. He uses organ donation as an example, where the default (opt-in vs. opt-out) significantly changes how many people donate. This ties to ideas on social infrastructure — the default design of public space influences so much of what happens in cities. Decision-making is costly in terms of time, money, and other resources, so we often default to patterns. It’s so important to be conscious of defaults in the environment — for decisions at an individual and societal level.

Leanna: The courses share a premise of examining the forces behind systems, whether in the way communities develop or the way we make decisions at an individual or societal level. An animating idea in both courses is knowing that things are not inevitable and seeking to better understand what shapes these systems. Our course explores forces that influence decisions such as childhood stressors, low socio-economic status, cognitive biases, or interpersonal relationships. Also, both courses integrate students’ experiences into academic theories, which I think is an important pedagogical tool.

What surprised you about teaching on Zoom?

Ros: Initially I was worried about how we would make the course experiential without site visits and in-person components of the course. But I was surprised — students would jump in and expand on each others’ ideas, making it possible to have really dynamic group discussions virtually.

Jackie: We found the breakout groups were great, in fact even more seamless than in-person where you have to shuffle chairs. We hit a button and students were instantly transported into spaces where they could carry on the conversation in small groups.

Leanna: I also loved the chat function. Students would type a thought that occured to them in response to a classmate’s comment or post links related to lecture. It was an excellent way to build off each others’ ideas without interrupting, and it added a layer of richness to the conversation.

Daniel: One thing that happened quasi-organically is that students asked for readings that hadn’t been assigned, but were mentioned in the course. We followed up each week by sending supplemental readings to allow students to dive deeper ideas on some of the topics.

Leanna: And students actually mentioned in the course feedback that they were glad we circulated additional readings…!

How does being an Artsci influence the way you taught the course?

Leanna: Consistent with the Artsci spirit of critical engagement, our course was structured to draw out some of the flaws in legal and machine decision-making processes. At the same time, there are ideas we find useful, both in critical disciplines like feminist theory and in more conventional approaches like the law. I was aware that the very design of the course can lead students to accept certain conclusions more readily than others, and was wary of suggesting there was one right answer. I did want to offer useful tools for decision-making though. The lack of disciplinary boundaries in Artsci is freeing and allowed us to include the ideas we found most stimulating.

Daniel: There’s an issue of breadth versus depth. Even in picking the readings, we asked ourselves how technical to get when students don’t all have a background in the area. We did a mix of introductory/survey readings and denser readings.

Ros: I agree, it was an ongoing challenge trying to figure out how much depth to go into on certain topics in a compact course without oversimplifying. Urban challenges are complex, and activities and group discussions often led to more questions than answers — which felt like a very Artsci phenomenon.

Jackie: What made Artsci so special was not only course content, but also the community and interactions you have with other students and professors. We thought a lot about how to foster those connections in our course. In previous years, they occurred in experiential components, but this year we were especially conscious of first years who aren’t living in Hamilton, and how the course could help them get to know upper years. It was important to create a course where students could come away feeling equipped to dig in, critique, and engage with issues in their communities, and feel more connected to one another.

Experiential LearningRelated News

News Listing

Artsci Student brings Hamilton war hero’s history to life

Experiential Learning, Students

April 22, 2024

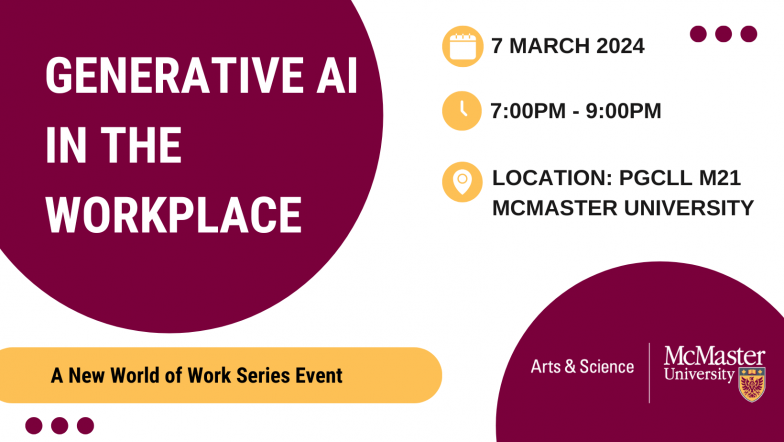

Exploring Generative AI in the Workplace – A New World of Work Event

Alumni, Events, Experiential Learning, Students

March 13, 2024

New World of Work Series Event: Generative AI in the Workplace

Alumni, Events, Experiential Learning, Students

February 6, 2024